Capability: The Friction Point You Think You Understand

Good training fails all the time. Here is why.

“Do I know how to do this?”

This is the question your people are asking themselves when they close the AI tool and return to the way they have always worked. Not because they are resistant. Not because they do not care. Because learning something new, genuinely new, while still delivering everything else, is hard.

Capability is the second friction point in the 5C Adoption Friction Model. If you have trained people and adoption is still stuck, the problem is rarely the training. It is the conditions that decide whether skills survive contact with real work.

You have probably already invested here. You have built resources, run sessions, brought in experts. And yet adoption remains flat. Not because you have done the wrong things, but because Capability gaps hide in places training cannot reach.

What Capability Actually Means

Capability is the ability to do real work with the tool, under real conditions, without excessive friction.

Not “attended training.” Not “has access.” Can this person complete their actual work using AI, when deadlines are real and mistakes cost time, credibility, or rework?

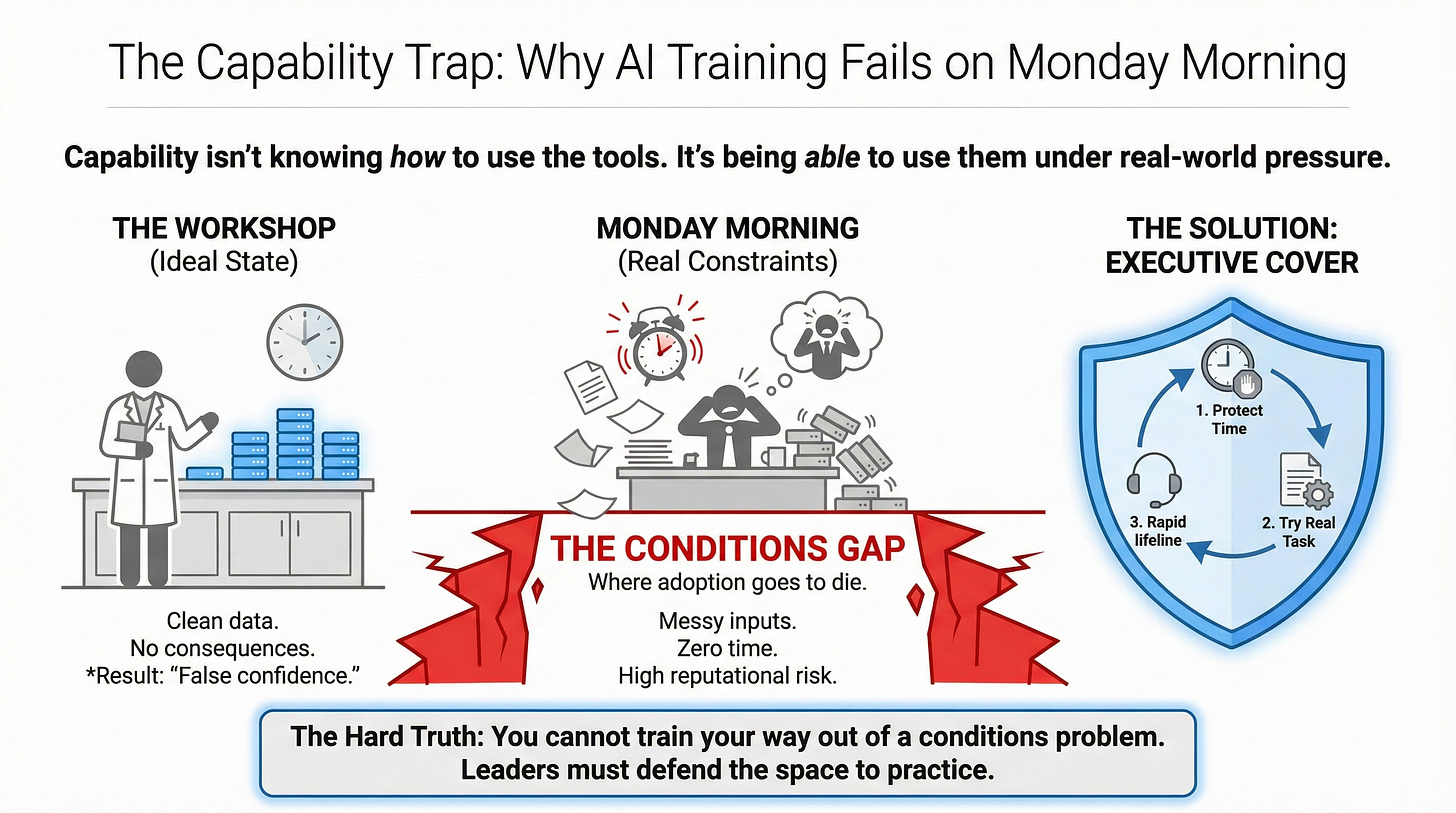

Training is slow, safe, and forgiving. Work is fast, high-stakes, and unforgiving. The gap between them is where Capability problems live. Skills that exist in the classroom often do not survive Monday morning.

Here is a diagnostic question: if you gave someone two uninterrupted hours with a real task and access to the relevant materials, could they complete it using the AI tool? If yes, Capability is likely not your primary blocker. If no, you have a genuine skills gap worth addressing.

How to Spot a Capability Problem

Here is how this typically plays out. It shows up as avoidance: people steer clear of the tools entirely, or they complete the training and never apply it. You hear “I don’t have time to learn this” or “It’s too complicated.”

But avoidance can signal different friction points. Here is how to tell them apart.

If people ask “what should I use this for?” that is not Capability. That is Clarity. They need to know the task before they need the skill to do it.

If people completed training and never applied it, with no confusion about what to do, the blocker is probably not skill. They may see no downside to ignoring the initiative, or they may worry about what AI means for their role. Both are covered in upcoming articles.

The clearest signal of a genuine Capability gap: noise. Attempts that fail. Error messages. Outputs that miss the mark. Frustrated questions about specific problems. “I tried to get it to summarise the document but it kept giving me something useless.”

Silence means avoidance. Noise means people are trying and failing. That is Capability.

Use these questions to separate can’t from won’t:

Can you point to one deliverable from the last fortnight where AI materially changed the outcome? If not, either skills are not transferring or something else is blocking usage. The next two questions help you tell which.

When someone got stuck last week, who did they ask within ten minutes? If the answer is “nobody,” your support system does not exist.

After training, do people attempt the task at least once? If they try and struggle, that is Capability. If they never try, something else is blocking them first.

What It Feels Like from the Other Side

This is the section most leaders skip, and it matters.

Being asked to learn something new while already at capacity is not neutral. It can feel like being told you are not good enough. It can feel like one more thing on a list that was already too long. It can surface old worries about technology, about falling behind, about being replaced.

People do not say this out loud. They say “I have not had time” or “It is not intuitive.” Underneath those words: embarrassment at struggling with something that looks easy, frustration at being asked to change when the old way worked fine, fear of looking incompetent.

This is worth sitting with for a moment. When you ask someone to build a new skill, you are asking them to be temporarily worse at their job. That is a vulnerable position. How much permission have you actually given them to be in it?

Why Training Often Fails

If you have invested in training and adoption is still stalled, look at what happened around the training, not in it. This is not about blame. Good training fails all the time because of conditions, not content.

Three patterns show up repeatedly.

The time problem: people learn on top of their existing workload, not instead of parts of it. Learning competes with deadlines. Deadlines win. The training happens Tuesday. By Friday, the pressure to deliver has erased whatever was learned.

The relevance problem: generic training on generic tasks. The examples do not match the work. People leave thinking “that was interesting” and cannot see how to apply it to the brief they are writing or the analysis they are running.

The practice problem: one-off sessions with no follow-up. Skills decay without use. Questions arise after the session ends, with nobody to ask. The moment someone most needs support is the moment they are most alone.

Notice the common thread. Each failure is about conditions. The training might be excellent. If the conditions do not support learning, the training will not stick.

What Better Conditions Look Like

Learning cannot compete with delivery. If you want people to build skills, you have to remove something else. Not “find time.” Create time. Protect it. Enforce it.

Consider what this might look like. A team of six attended AI training a month ago. Two use the tools regularly. Four do not.

A conditions-focused approach: for three weeks, Friday afternoons are protected learning time. No meetings, no deadlines due. Each person picks one task they must deliver the following week and attempts it with the AI tool. Someone already using the tools is available for questions. At the end of each Friday, the team spends fifteen minutes sharing what they tried: the task, the prompt, what worked, what broke. These get captured in a shared doc, building a library of real examples from real work.

No new training. No extra content. Just protected time, real tasks, someone to ask, and a way to capture what is learned.

This is where most implementations stall. The first Friday goes well. The second gets squeezed by a client deadline. By week three, someone senior asks why the team is “unavailable” on Friday afternoons. Protected time requires protection, and protection requires political capital most middle managers do not have. If you do not have explicit backing from above, the conditions will erode before the skills take hold.

It also means managers need new skills. Most know how to assign work and review output. Fewer know how to create safety for learning, coach through frustration, or hold space for someone to be temporarily worse at their job. If your managers have not built this capability themselves, the conditions will not hold.

The question to ask yourself is this: have you given people time and space to learn, or is AI adoption something they are expected to do on top of everything else? And if you have created the conditions, do you have the backing and the management capability to sustain them?

What Success Looks Like

When Capability work succeeds, the change is visible.

Questions get specific. Instead of “How do I use this?” you hear “How do I get it to keep the formatting?” The shift from general confusion to specific refinement signals baseline skill is in place.

Experimentation spreads. People try the tools on tasks they were not told to try. They extend what they learned rather than repeat it.

Failure becomes speakable. People share what did not work without embarrassment. They ask for help openly. The vulnerability required for learning no longer feels risky.

Output shows evidence. Tighter writing. Faster turnaround. Analysis that would have taken twice as long. You can see AI contribution without anyone mentioning it.

In most knowledge-work teams, you should see early signals within three to four weeks of creating the right conditions. If you do not, revisit your diagnosis. Capability may not be your primary blocker.

Where This Leaves You

Capability is real. When people genuinely lack skills, no amount of clarity or consequence will help. They need to learn. And they need conditions that make learning possible.

But Capability is also the comfortable diagnosis. It lets leaders focus on training programmes instead of harder questions about clarity, credibility, or consequences. Before assuming Capability is your blocker, check Clarity first. Can people describe, in specific terms, what they are supposed to do differently? If not, start there.

If Capability is genuinely the gap, the fix is not more training. It is protected time, real tasks, someone to ask, and a way to capture what works. Simple to describe. Hard to sustain.

Paid subscribers get the Capability Playbook: the diagnostics, the conditions loop, and the templates to capture what works. If your real problem is political cover and manager coaching, not content, the AI Change Leadership Intensive can help you build the backing that makes the conditions hold.